All the estimates of Springfield's Haitian population are wrong

Forget the sensationalized reports. The real figure is much smaller.

Just how many Haitian immigrants have moved to Springfield, Ohio, in recent years? It's a question at the center of the new national discussion about the city's resurgence and ensuing struggles to accommodate its new growth. There's no definitive answer, but we can say this: Almost every estimate you've seen is wrong—and too high.

In particular, the oft-quoted figure that 20,000 new residents from Haiti have settled in Springfield is not accurate. The real number is likely around half that amount. Here's how we know.

After shrinking dramatically over the last half-century, Springfield has worked hard to revitalize emptying neighborhoods by attracting new residents and workers. By all accounts, this civic revival is succeeding. Springfield's population peaked at more than 80,000 in 1960 but then began a continuous decline, falling to under 60,000 in 2020. But that decline appears to be leveling off as the city experiences what the local newspaper called in 2022 a "resurgence."

Newcomers from Haiti have played a critical role in this transformation, and their actual number is likely more in line with official estimates in the low five figures. But even these assessments may be too large: New data from the Census Bureau shows only a tiny increase in Springfield's Haitian population, though it, too, has sources of error, and comes to us already a year out of date.

As Haitians in Springfield experience an outpouring of hatred fomented by the far right, it's reasonable to ask why we might be concerned with precise population counts. Accurate data, however, is at the heart of responsive democratic governance. Cities, counties, states, and the federal government all need detailed information about their inhabitants if they're to meet the needs of longtime residents and new arrivals alike.

Conversely, repression of the facts is a key page in the authoritarian's playbook. The absence of trustworthy data creates an information vacuum easily filled by propaganda. That gap is already being exploited. The Downballot's goal is to close it.

The Media vs. City Officials

A critical problem is that some of the most frequently cited figures of the Haitian population in Springfield are thinly sourced and are at odds with official sources. For instance, many media reports, including an in-depth profile of the city in the New York Times, have said that as many as 20,000 Haitian immigrants have moved to the city in recent years. Fox News, meanwhile, went as high as 30,000, a claim attributed solely to a Springfield resident.

The Times cited unnamed "city officials," but other officials who've gone on the record—including the city's Republican mayor—say the number, while still a substantial proportion of Springfield's total population, is considerably smaller.

For instance, the local Springfield News-Sun reported this week that the actual number is "more around 12,000–15,000." That statistic was provided at a recent press conference by Mayor Rob Rue, who said it came from "the health department and other agencies."

But the number may be smaller still. Rue was answering a reporter's question about the Haitian population in the "Springfield area," which extends beyond city limits. Data from the city indicates that Rue was indeed speaking of the wider region. On a page of "Immigration FAQs" on Springfield's official website, the city says that "the total immigrant population is estimated to be approximately 12,000–15,000 in Clark County," the county where Springfield is located.

Since those numbers are identical to Rue's, it's likely he was referring to the same estimate provided on the city's website. Those figures, however, don't specify how many immigrants are Haitian. They also cover all of Clark County rather than just Springfield, which makes up about half the county. So even if most live in Springfield and most are Haitian, the number of Haitians in Springfield would be smaller than these overall figures.

The Census Bureau Weighs In

Meanwhile, new data from the Census Bureau, which just days ago released updated population estimates from its American Community Survey, doesn't seem to have picked up on recently described trends at all. However, there are good reasons not to take this data as gospel either, which we'll get to in detail below.

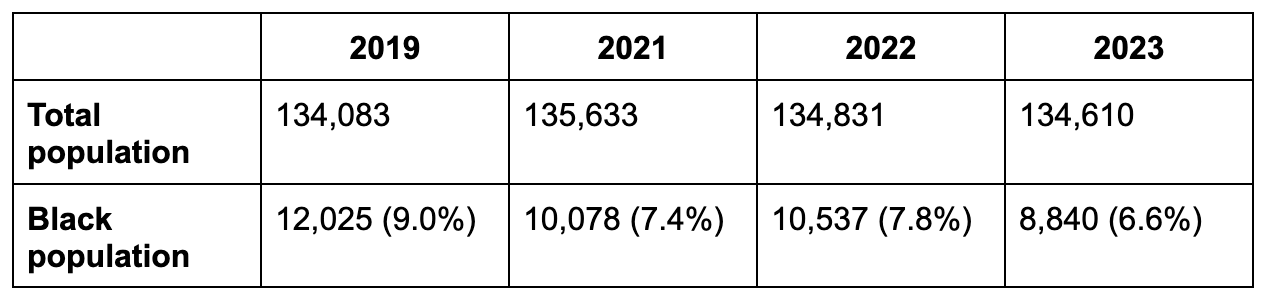

For example, the population of Clark County appears to have remained flat from 2019 to 2023, contrary to claims that tens of thousands of new residents have overburdened the local infrastructure. And the county's Black population in particular has actually fallen during that same timeframe, indicating that out-migration and deaths may be outstripping any in-migration and births.

(We use data from the county, which has a total population of about 135,000, rather than from Springfield because the city is not large enough to be broken out separately in the Bureau's annual updates. The links to the data we cite are provided at the bottom of this piece.)1

The American Community Survey, which the Census Bureau undertakes every year to gain a better understanding of population trends between each full-blown decennial census, allows us to dig even deeper.

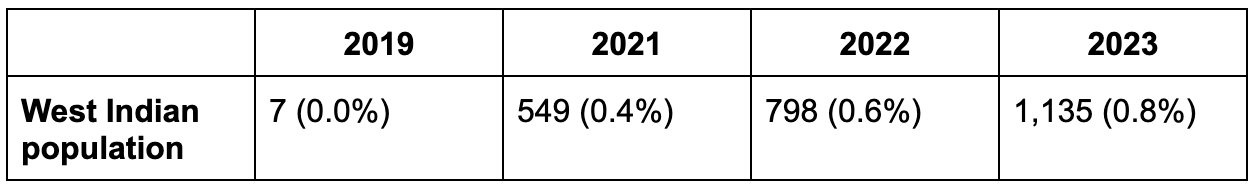

In particular, the ACS goes beyond race to ask about ancestry and national origin. We can therefore see specifically how Clark County's West Indian population has changed. ("West Indian" is how the Census Bureau categorizes ancestries in the Caribbean region, including Haitian.)

While the increase looks huge relative to its starting point of just seven persons five years ago, West Indians have not yet become a significant portion of the population as a whole: The latest ACS data shows the community making up less than 1% of the county. (Other data from the ACS confirms that the vast majority of West Indians in Clark County are indeed from Haiti.)

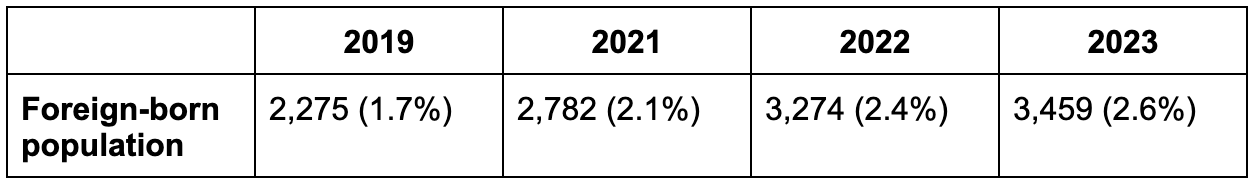

There has been a perceptible influx into Clark County of foreign-born persons of all origins from 2019 to 2023. However, the ACS finds this increase in the low single-digit thousands (and note that these figures include naturalized U.S. citizens as well as individuals who may have lived in the county for many years).

Schools, Jobs, and Housing

One frequent claim about Springfield (and other cities that have experienced similar trajectories) is that population growth has put undue stress on the local school system, especially in terms of additional resources for English-language learners. The Sun-News has regularly reported on the challenges schools face thanks to these new students.

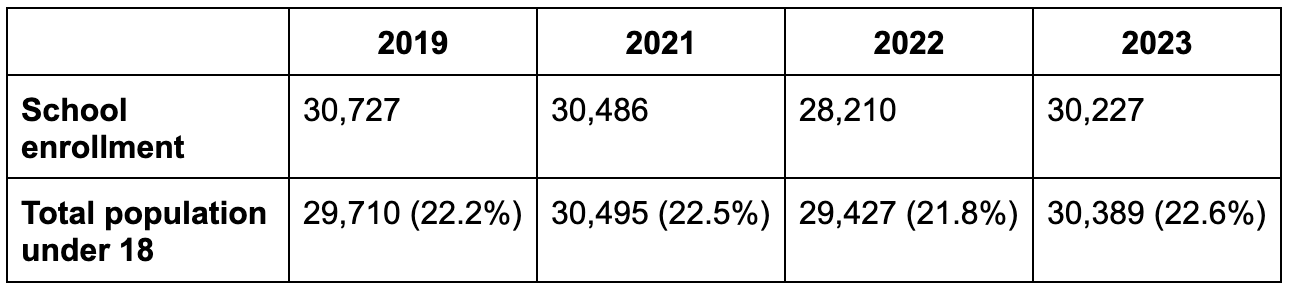

These challenges are real, but interestingly, ACS data does not indicate an increase in Clark County's total school enrollment from 2019 to 2023, or even a notable increase in the overall under-18 population.

Enrollment figures (apart from an unexplained blip in 2022) may be flat despite an increase in the number of Haitian pupils if other groups of students are declining.

(Note: The ACS school enrollment figure includes post-secondary education, such as community college or four-year college, which explains why the school enrollment number can exceed the under-18 number.)

Similarly, there have been allegations of negative economic consequences for long-term residents. These generally take the form of two contradictory claims: either that immigrants are taking jobs that would otherwise go to longtime Springfielders, or that they're not working and living off public assistance.

Neither of these claims are supported by ACS data, which is on firmer territory when it comes to statistics that enumerate all of Clark County's residents as opposed to those that attempt to count subsets, like residents of West Indian origin.

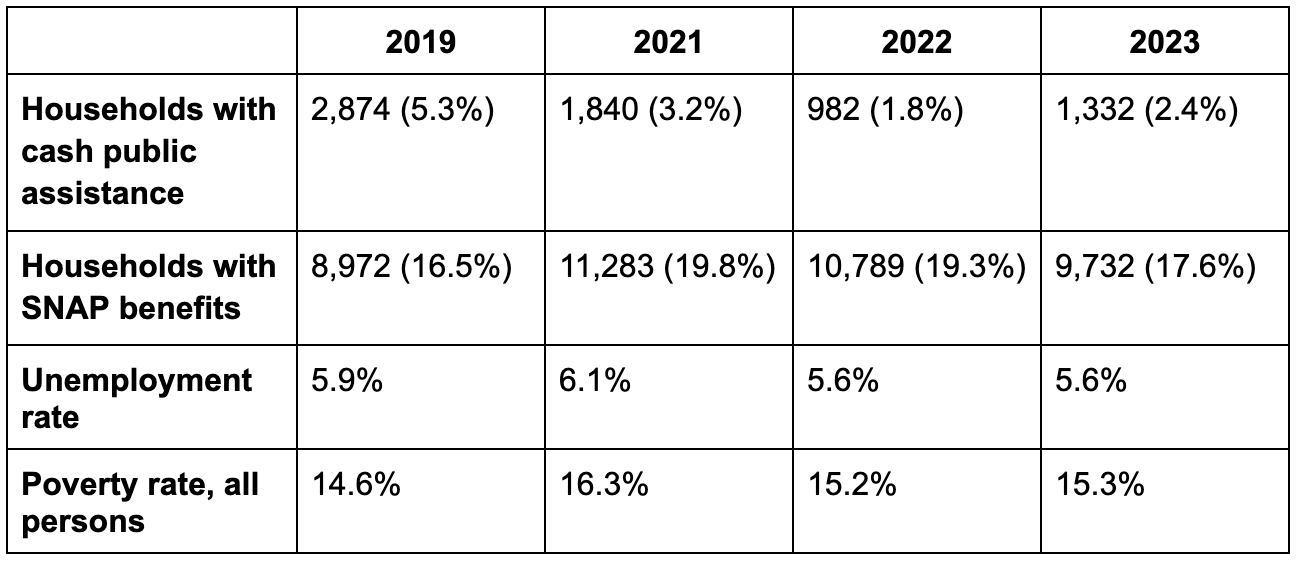

Since 2019, the percentage of county households receiving cash public assistance has been halved, and usage of food stamps has increased only slightly. More generally, the unemployment rate and the poverty rate in Clark County have remained flat throughout.

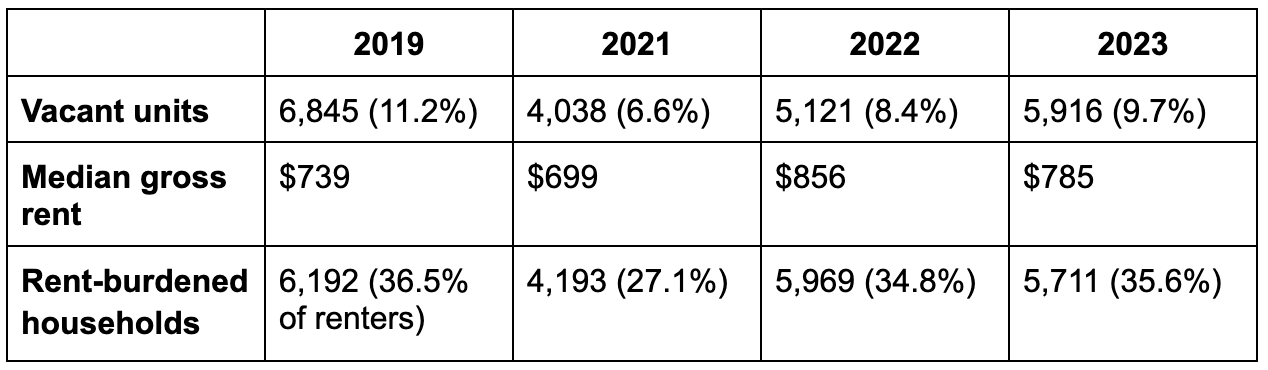

Some have argued that the large increase in the population has put stress on the local housing market, driving up demand, increasing rents, and pricing out longtime residents. However, ACS data indicates that the vacancy rate in Clark County has fallen only slightly from 2019 to 2023, by around 1.5 percentage points. (A lower vacancy rate indicates greater demand and projects increasing prices.)

While rents have increased, they've done so at a much lower rate than the national average. Clark County's median rent grew 6% between 2019 and 2023, but during the same timeframe, the national median rent jumped 28% (figures are not adjusted for inflation).

In addition, the percentage of rent-burdened households—how the Census Bureau categorizes households that spend 35% or more of their income on rent—actually fell during this time period.

The Problems with the Data

So what could explain the significant differences between the formal data about Clark County from the Census Bureau, the estimates from city officials, and the more dramatic narrative depicted in media accounts?

For starters, the ACS isn't capable of providing instantaneous answers about real-time population numbers. Although most news coverage has described the increase in Haitian immigration as occurring over the last two, three, or five years (depending on who's doing the reporting), it's possible that the bulk of the influx took place this year. If that's the case, then the small upticks that we saw in the 2022 and 2023 data were only the tip of the proverbial iceberg.

That possibility has some support from multiple news accounts from mid-2023 that put Springfield's Haitian population at approximately 4,000 to 7,000. That's still very different from the ACS estimates of roughly 1,000 such immigrants through 2023. But if the media assessments from a year ago were correct, then the city's reckoning that the community is today in the low five figures would be plausible if Springfield added a few hundred new Haitian residents per month since the middle of last year.

Another consideration is that the Census Bureau has, notoriously, long had trouble counting hard-to-reach populations. The Bureau breaks this category down into several sub-groups, including those who are hard to contact (people who are mobile and may not have a fixed address); those who are hard to interview (people who may face language or technological barriers); and those who are hard to persuade to participate (people suspicious of the government and with low levels of social trust).

Recent immigrants, especially those experiencing hostility from their local community, could fall into any or all these categories.

In other words, the Bureau may simply be unable to keep up with the pace of Springfield's population growth and the resulting changes in education and housing.

Why the Real Number is Likely Around 10,000 (Give or Take)

At the same time, though, economists have started noticing that other, more responsive data are still showing a similarly flat trendline in the Springfield area. This includes employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as flagged by analyst Kevin Erdmann, which is reported monthly (versus the ACS, which comes out annually).

Still other data sources suggest notable growth among the Haitian population, but they all start from a small baseline, and their current total remains relatively low.

For instance, records from the Springfield City School District, reported earlier this year by the News-Sun, showed a 12.5% increase from the 2022-23 school year to the 2023-24 school year in the number of students classified as English-language learners. There are 927 such pupils (out of about 7,700 total in the district), a group that accounts for speakers of all foreign languages, including French and Haitian Creole as well as Spanish.

The nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute meanwhile finds that 7% of Haitian immigrants to the United States are under the age of 18 (which incidentally is a much smaller share than the 24% of the U.S.-born population that's below 18). Using that 7% proportion as a guideline, we can expect the Haitian community to number roughly 10,000 based on the number of kids enrolled in school, since it's likely nearly all are English language learners.

Similarly, public health officials in Springfield reported a significant increase in Haitian patients in the period from 2021 to 2023, according to the Times. Again, though, the raw numbers offer important context, growing from just 115 three years ago to 1,500 last year.

State Medicaid rolls, meanwhile, show an expansion of the covered Black population in Clark County from about 6,600 unique monthly recipients in 2019 to a high of 15,200 in June 2024. This increase is about 7,000 more than what might be otherwise expected if the county’s rolls had increased at the same rate as the state’s rolls.

It's not clear how quickly people tend to leave Medicaid, and not all immigrants have necessarily joined the program, so we can't develop an estimate of the Haitian population based solely on this figure. That baseline of 7,000 enrollees is higher than the ACS count of West Indians, but also nowhere near the numbers touted by national media.

More simply, if we take the county's current official estimates for all immigrants (around 12,000 to 15,000) and subtract the ACS estimate of the total foreign-born population prior to extensive Haitian immigration (approximately 2,000 in 2019, which is itself likely to be an undercount), that also suggests a total Haitian community of around 10,000.

Again, these numbers are for Clark County as a whole, so the figures for Springfield itself would be lower. They are also estimates, so the total we've arrived at could be somewhat greater or somewhat smaller.

None of this is to minimize the challenges Springfield faces. To the contrary: The city needs the best possible understanding of those who live there in order to serve them properly—and that includes understanding, to the best of anyone’s ability, how many new arrivals from Haiti that includes.

This foggy information environment emphasizes how important it is that the media—especially national publications with large readerships—slow down and dig into the data. Reporters should be wary of passing along statistics tossed out by local officials or repeated in thinly sourced news accounts without vetting them carefully.

If nothing else, the many official sources pointing to a much smaller influx of Haitian immigrants suggest that the more alarming-sounding estimates may have been spoken into existence through a game of telephone—much like the swiftly debunked stories of animal abuse that originally drove the media interest in Springfield.

One-year ACS data for Clark County, Ohio from the Census Bureau:

Data is not available for the 2020 1-year ACS (for any geography) because of interruptions to data collection due to the pandemic.

I wonder how many of the immigrant Haitians are Catholic, given that 65% of Haitians are Catholic. Might be worth asking Vance why he is baselessly attacking fellow Catholics.

Wow, great job. Now if we can just get the national media to report facts instead of "vibes" or what some rando posted on Facebook...